By Kirsten Cave

February 2021

Danny Fox: The Sweet and Burning Hills (January 12-February 26, 2021) at Alexander Berggruen, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

I have always used photographs as source material for figurative painting. In recent years the iPhone has been a well used tool, but I’ve always liked to look back to early Parisian studio photography, predominantly from the late 1800s. The erotic photographers of their day referenced classical paintings for the model poses, then the painters working at this time would buy these images in the form of early pornographic postcards and use them as painting and drawing reference, completing a feedback loop of visual reference.

Danny Fox

Shortly after the daguerreotype was invented and publicized in 1839, painters recognized photography’s merits. The first well-known painter to publicly share the idea that photographs were a useful source for painters was Eugéne Delacroix (1798-1863). Delacriox worked in collaboration with his friend, photographer Eugéne Durieu (1800-1874). In Paris, in 1853 and 1854, Delacroix directed models to pose, and Durieu photographed them via a wet-plate process. Their collaboration formed the earliest connection between nude photographs and a group of related drawings and paintings (1).

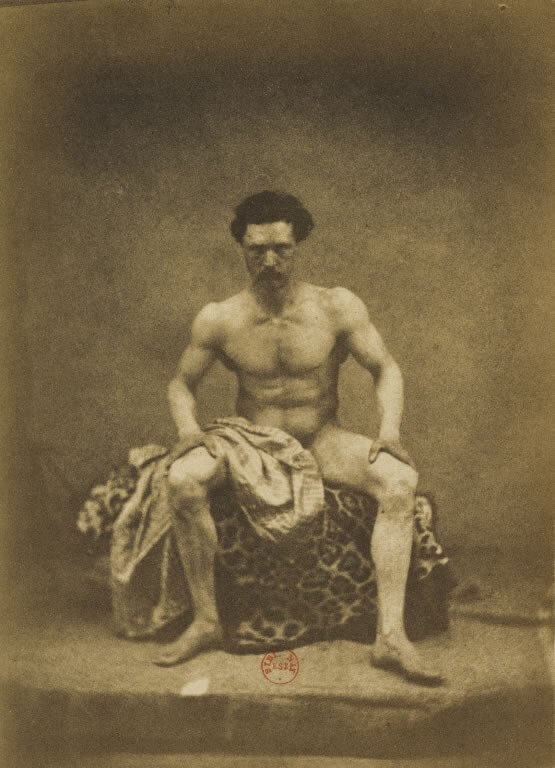

Eugéne Durieu, Studies, 1854. Photograph. Musée Bonnat, Bayonne, France.

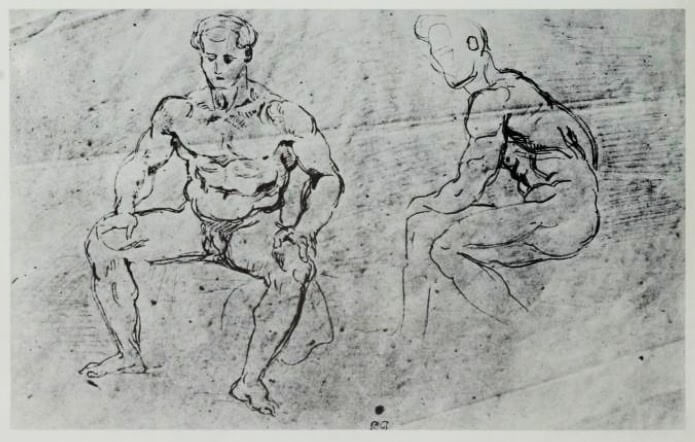

In Durieu’s 1854 Studies of a seated male nude, a man sits on a pedestal, leaning slightly forward toward the camera with his hands rigidly grasping his legs and his elbows turned out to the side. His head is tilted down as he intensely gazes up at the viewer from underneath his eyebrows. In Delacriox’s accompanying 1855 drawing, this male figure appears slightly more relaxed, turning his face away from the viewer, eyes cast downward in one pose, and resting his hands more gently on his legs in another. However, Delacriox preserved the figure’s open posture.

Eugéne Delacroix, Studies, 1855, pen and ink drawing, 9 ½ x 13 ¾ in. (24.1 x 34.9 cm.). Musée Bonnat, Bayonne, France.

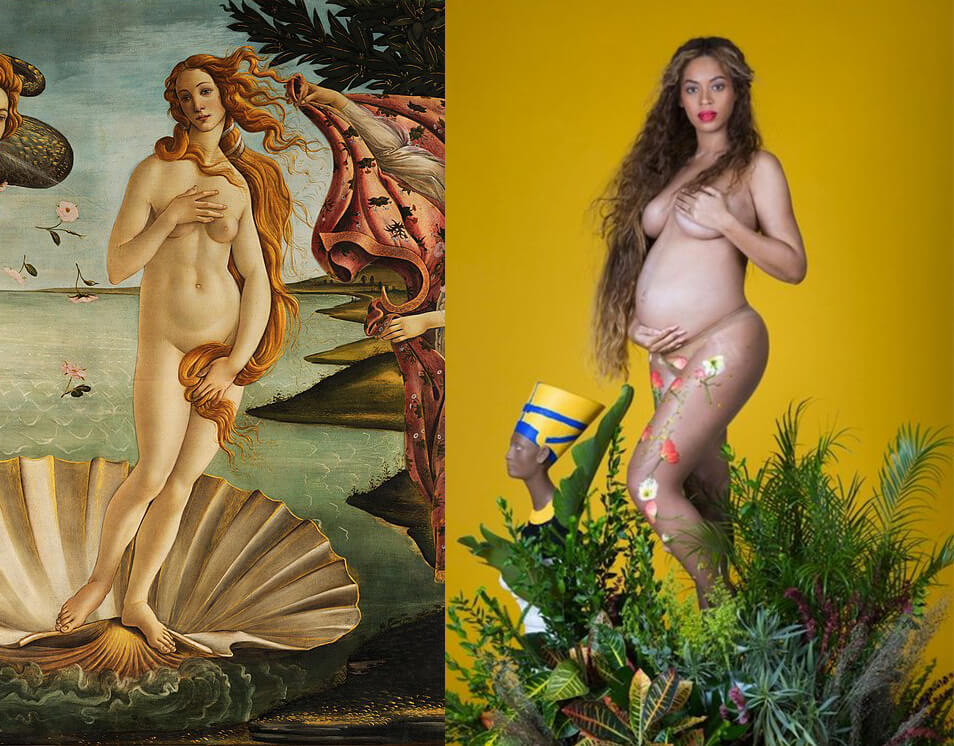

With developments in photography over the remainder of the 19th century and beyond, not only would painters glean visual stimuli from photographic portraiture, but photographers would also compose stills based on paintings, or even incorporate paintings as the subject matter. In recognizing the success of classical nude portraiture, portrait photographers have often posed their models to recall canonical postures, such as Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485–1486) (2). The Birth of Venus pose was replicated in early photographic pornography and is still imitated in today’s pop culture, as seen, for instance, in Beyoncé’s 2017 pregnancy photo announcement on Instagram. Further intertwining photography and painting, Louise Lawler (b. 1947) of the Pictures Generation photographs artworks in the context of their settings outside of the artists’ studios. In Lawler’s photograph Salon Hodler (1992, printed 1993), two late 19th century paintings by Ferdinand Hodler, which portray couples embracing, are shown on display in the home of a Swiss private collection. Finding inspiration in each other’s medium, photographers and painters have a history of operating within, as Fox stated, “a feedback loop of visual reference.”

Beyoncé (right) invokes The Birth of Venus (1485–1486) by Sandro Boticelli (left). Beyoncé photo: Instagram.

From 1851 through the 1860s in France, the government imposed strict censorship on the sale of pornography. Authorities drew an ambiguous differentiation between nude photographs as pornography versus as artistic observation. The transaction of such photographs was only allowed under the title of academic study, “within the walls of the École des Beaux-Arts” (3). Once restrictions on the sale of nude photography were slightly loosened by the 1890s, postcards with nude images became widespread and “formed an important part of that commodity culture” (2). In popularizing poses of paradigmatic odalisques, the gap between high art and low art narrowed as the same poses and symbols of female nudity permeated both the walls of the salons and the racks of drug stores (2).

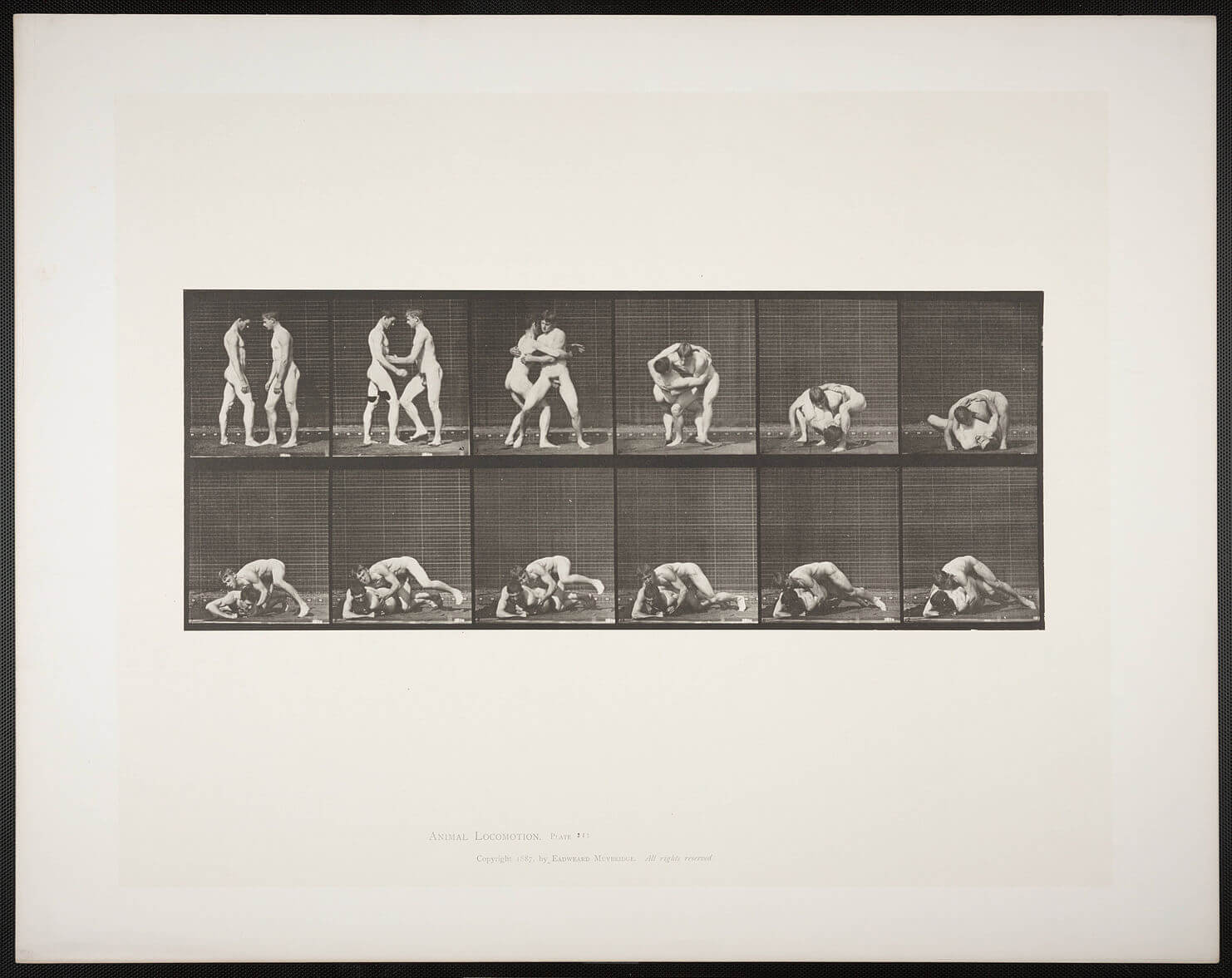

Eadweard Muybridge, Nude men wrestling, lock, 1872-1885. Plate 345 from Animal Locomotion (1887), 1884-1886, collotype on white wove paper, Image: 6 ¾ x 17 ¼ in. (17.4 x 44 cm.) Overall: 19 x 24 ¼ in. (48.3 x 61.4 cm.). George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

Photography’s ability to capture and flatten the exact details of a precise moment can provide painters with unique source material. Photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) revolutionized the use of photography to study exact anatomical movements. He published books on a series of photographs of people and animals performing various activities in the 1880s, including one titled Animal Locomotion (1887). This opportunity to study distinct still positions of a body in motion influenced, and continues to influence, artists including: Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905), Jules Dalou (1838-1902), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), and post-war and contemporary artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), Francis Bacon (1909-1992), and Jenny Saville (b. 1970) (1).

Through photography’s ability to record authentic lines, shapes, shadows, and forms, what may also be captured is the feeling, presence, and spirit of a subject. When Fox employs a photograph as source material, he extracts and emphasizes the most essential aspects. What the painter preserves, excludes, and changes “can illuminate the nature of the artist’s modus operandi, thus shedding light on the creative process” (1).

In Fox’s recent body of work, he created his own source material in collaboration with photographer Kingsley Ifill. Together, in the winter of 2019 in Beachwood Canyon, they compiled Ifill’s photographs and Fox’s drawings, and their collaborative works, into a book, Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof, published by Tarmac Press in England. The artists’ friends from the Hollywood Hills acted as their models, often holding poses reminiscent of Renaissance odalisques and nude photography of the late 1800s.

Danny Fox, Lorraine with Teapot and Candles, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 in. (152.4 x 182.9 cm.). Photo: Dario Lasagni.

In response to the nude female form on display in Ifill’s photographs and Fox’s drawings and paintings, a viewer may wonder about the possibility of female objectification. Should this be read as a celebration of the innate beauty of the female form, or could it be read as an exploitive function under a patriarchy, as has often been the case in the past? To answer the question, one of the subjects from the series, Lorraine Nicholson, wrote in the introduction to Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof:

I agreed wholeheartedly, more comfortable, like many of the women contained in these pages, on the other side of the camera. After all, the people captured in this book are creators in their own right. There was a deliberate knowledge, for all of us, that we were in direct conversation with the objectification of women and cancel culture, global warming and misconduct in the arts. In today’s world, even doing a decent thing can feel like a rebellious act. [..] Here we answer a very contemporary question: who, in their right mind, would subject themselves willingly and on purpose? The answer, of course, is creators. Objectifiers in their own right who understand the delicate ecology of the artist and muse. (4)

In discussing the book, Fox shared that the paintings from his current solo exhibition at Alexander Berggruen The Sweet and Burning Hills “derive from these images, figuratively speaking,” as can be seen when comparing many of the images with several of the paintings in the show.

Fox painted Honor with Burning Hills based on a version of Ifill’s seated photographs of friend and fellow artist Honor Titus. Similar to Dureiu’s and Delacroix’s studies of the male nude, Fox and Kingsley modelled Honor seated with his legs open, slightly hunched and leaning forward. In Ifill’s photographs, Honor’s bent arms and defined neck tendons cause him to appear tense. Similar to how Delacroix softened his study of a male nude by rendering his arms and face more relaxed, Fox too exaggerated the slouch of Honor’s left shoulder, painted his collarbones a bit more forward, and excluded definition in the figure’s neck to imply a more slack position.

Danny Fox, Honor with Burning Hills, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 in. (152.4 x 182.9 cm.). Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Working from Ifill’s black and white photographs, the colors Fox chose are markedly his own. Fox refrained from adding whites to Honor’s eyes and, instead, rendered them brown with a strong flash of blood-red in their corners. Perhaps Honor’s eyes have become reddened from the smoke emanating from the burning trees behind him, absent in the photographs but rendered in acrylic in Fox’s own interpretation of the scene. Honor’s slouched posture and bloodshot eyes may seem to portray him as dejected. Fox imbued an added complexity into the figure–a tension between the fleeting, youthful beauty of those who live in Hollywood and nature’s own beauty, endangered by forest fires and human presence.

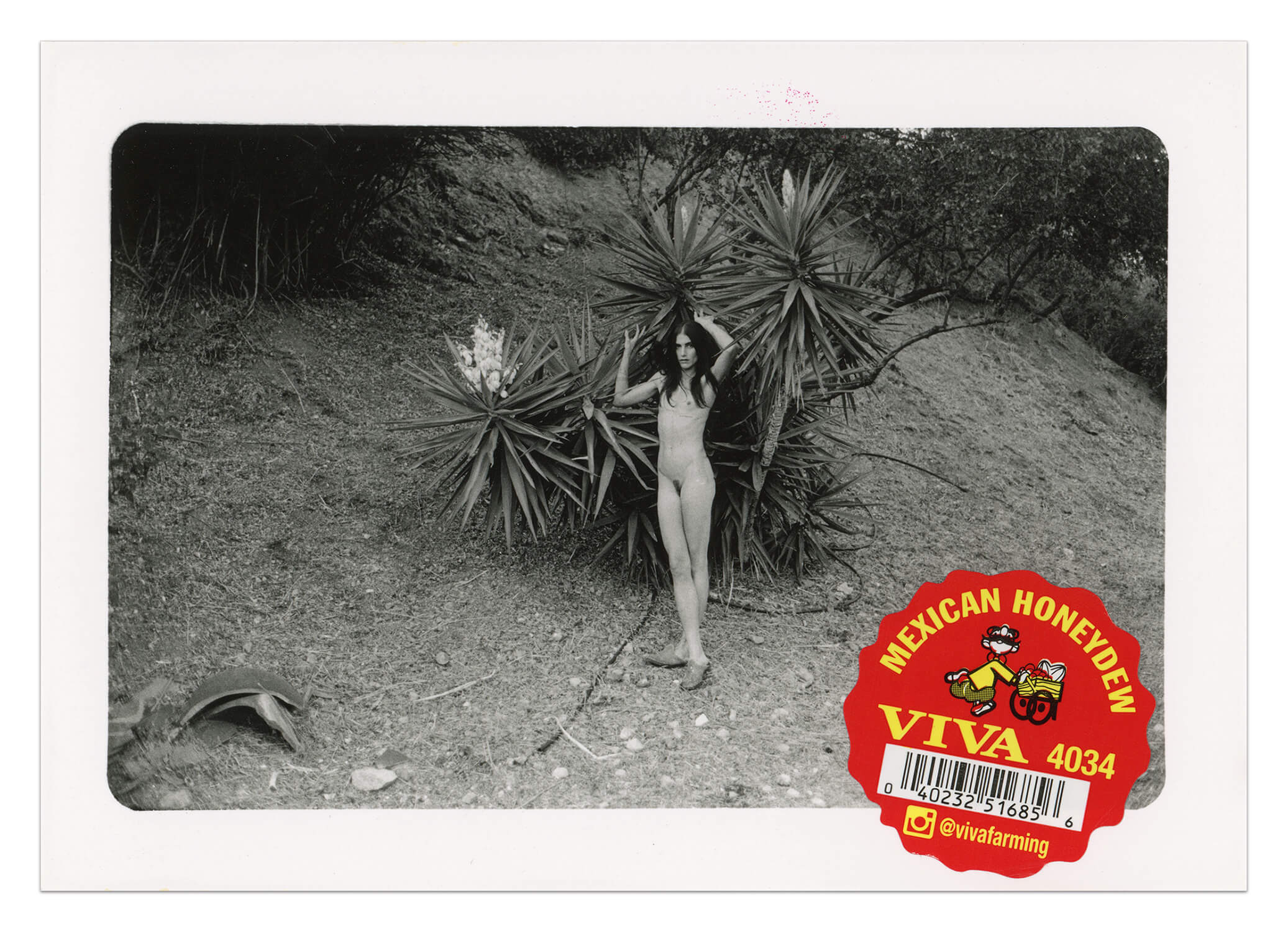

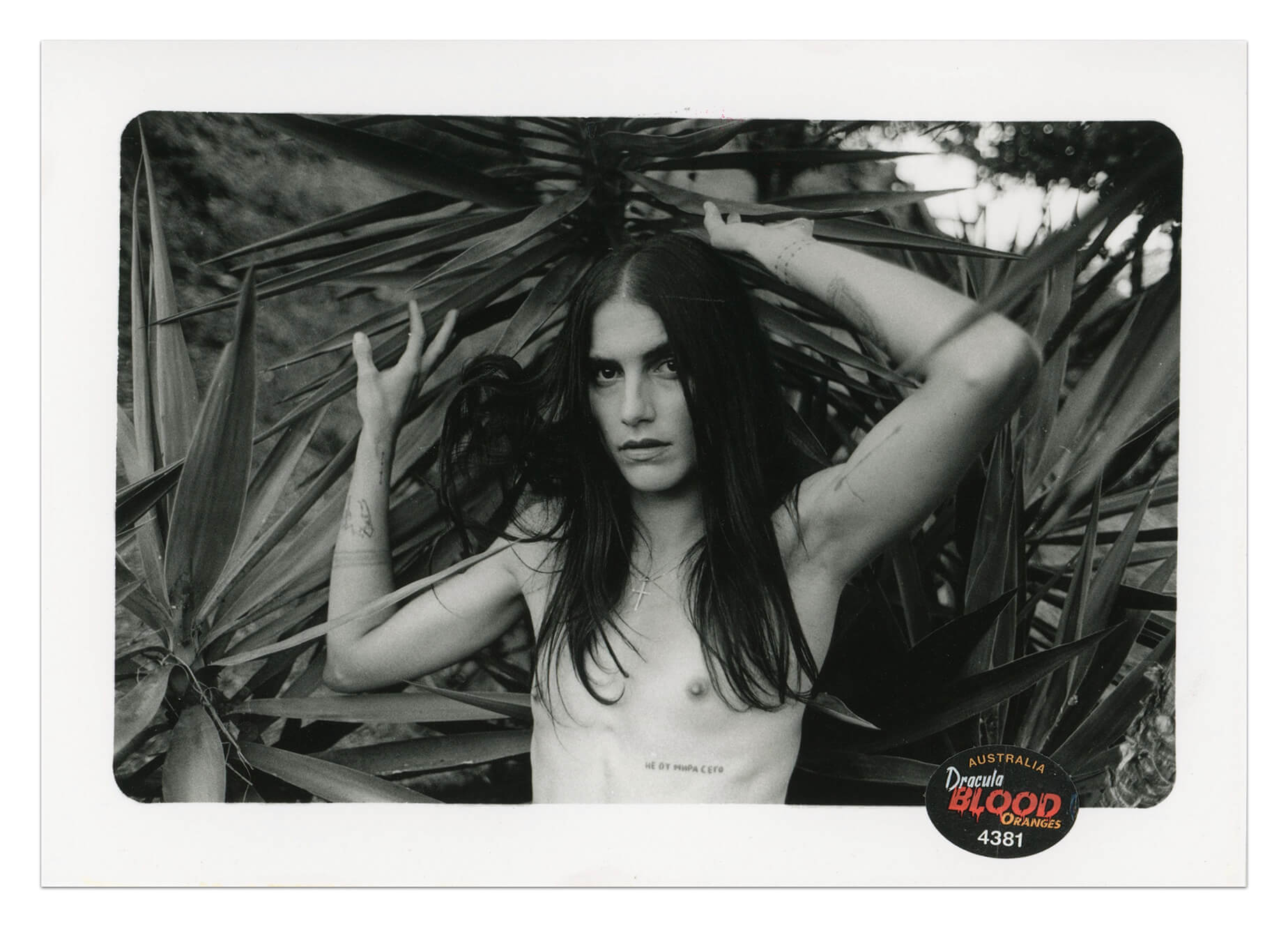

Kinsley Ifill, Photo of Langley Hemingway, 2019.

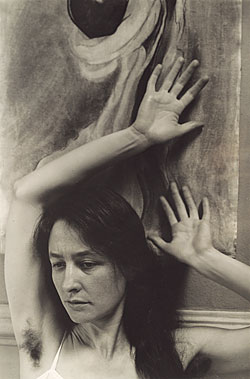

Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof also features three photographs of Langley Hemingway in the garden, in the same position: her arms raised and bent amidst a Yucca flower tree. In the days leading up to this photoshoot, Ifill mentioned that he was reading a book about Alfred Stieglitz’s (1864-1946) photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and became inspired by Stieglitz’s “delicate portrayal of hands.” In a series of 1918 photographs of O’Keefe by Stieglitz, she leans against a wall with her arms raised above her head, quite like Langley’s. This arm position also recalls photographs by Guglielmo Pluschow (1852-1930) who, in Ifill’s words, is “A master of the elbow, if there ever was one.”

Alfred Stieglitz, Photograph of Georgia O’Keefe, 1918.

Kinsley Ifill, Photograph of Langley Hemingway, 2019.

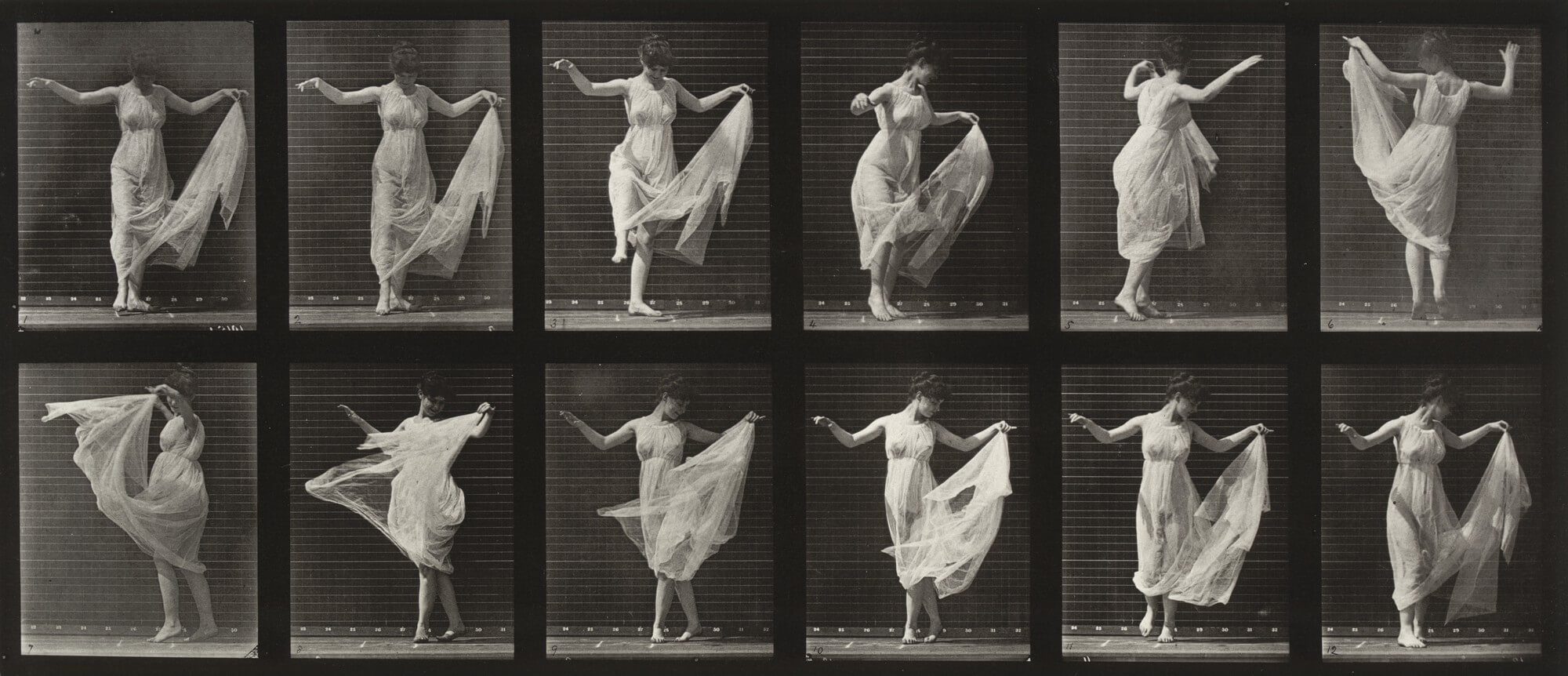

Of the three photographs of Langley, one is close-up, cropped at the bottom of her sternum. The other two photographs are from further away, revealing her whole body–one in portrait orientation and one in landscape. Fox combined the three to produce his ideal composition: horizontal and cropped at the bottom of her torso, where he omitted her crossed legs. The subject’s pronounced pubic “v” appears, as it did in many of the nude female models’ poses on postcards and paintings from the mid to late 1800s. Her pose–arms raised above her head, legs crossed tightly, right toe pointed–is particularly reminiscent of a motion photo titled Woman Dancing (Fancy) (1884-1886) included in Eadweard Muybridge’s book Animal Locomotion (1887). Similar to Langley’s pose, several stills in Muybridge’s Woman Dancing (Fancy) catch the dancer with her arms bent and raised up in line with her head and legs crossed, mid-twirl.

Eadweard J. Muybridge, Woman Dancing (Fancy): Plate 187 from Animal Locomotion (1887), 1884-86, Collotype, 7 1/4 × 16 ¾ in. (18.4 × 42.5 cm.). Museum on Modern Art, New York, NY.

In the photographs of Langley in the garden, Langley’s head is tilted. With one eyebrow slightly raised, she looks up out of the corners of her eyes to meet the camera’s gaze. Fox extracted Langley’s inquisitive glance, but turned her chin so that she looks straight out of the canvas, almost as though the painting is aware of an external presence. Fox preserved Langley’s arm positions above her head, palms turned out to hold the leaves surrounding her. In fact, Fox even maintained the foreshortening in the position of her right hand, showing only three fingers. Instead of the rigid leaves that surround Langley in the photograph, Fox enhanced the garden with more free-flowing curving plants that curl around Langley’s fingertips, emphasizing her connection to nature.

Danny Fox, Langley in the Garden, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 in. (152.4 x 182.9 cm.). Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Using photography as source material enables Fox to extract the lines, forms, and layers that comprise the simplest rendering of his subjects’ lives and spirits, and to synthesize them to their core essence. Following a long lineage of visual artists, Ifill’s photographs and Fox’s drawings and paintings are each a unique destination along the continuing feedback loop of portraiture. In permutations of this feedback loop, discrete voices evolve, and similarities arise–artists may elicit and build upon timeless manifestations of humanity.

Danny Fox: The Sweet and Burning Hills (January 12-February 26, 2021) at Alexander Berggruen, New York. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Bibliography

(1) Van Daren Coke, The Painter and the Photograph: from Delacroix to Warhol, Albuquerque, 1964, pp. 1, 7-9, 159, 166.

(2) Lisa Z. Sigel, “Filth in the Wrong People’a Hands: Postcards and the Expansion of Pornography in Britain and the Atlantic World, 1880–1914” in Journal of Social History, vol. 33, issue 4, July 1, 2000, pp. 859–885. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2000.0084

(3) Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “The Legs of the Countess” in October, vol. 39, 1986, pp. 65-108. www.jstor.org/stable/778313

(4) Lorraine Nicholson, “Introduction” in Eye For A Sty, Tooth For The Roof, London, 2020.