Sholto Blissett, Emma Fineman, Madeline Peckenpaugh (December 10, 2021-January 22, 2022) at Alexander Berggruen, New York.

On the occasion of our exhibition Sholto Blissett, Emma Fineman, Madeline Peckenpaugh (December 10, 2021-January 22, 2022), we spoke with the artists about their work.

London-based artist Sholto Blissett constructs fantastical landscapes, marked by imagined monuments and topiary in the foreground. They are eerie scenes suffused with the tension between human attempts to modify nature, and nature’s resistance to these contortions.

Sholto Blissett

Garden of Hubris XX, 2021

oil on canvas on board

43 1/4 x 59 in. (110 x 150 cm.)

Q: Between the grand, fog-covered mountains in the distance, the greenish bodies of water, and the mossy coastline, the environments depicted in your paintings appear distinctly European. From where do you draw inspiration for your fantastical landscapes?

My inspiration has always come from places I have been throughout my life. These are predominantly European: visiting, as a child, the west coast of Scotland and various Swiss valleys. More recently, I’ve expanded my horizons by going to northern Norway and New Zealand.

But at the same time, these landscapes are highly imagined – as you say: fantastical. The reason for this being that I am inspired by the possibilities of art itself: what could I do with a paintbrush? I enjoyed embellishing those places I’d seen; so much so that as my work now stands, that elaboration has become pure creation. I wasn’t aware that in this act, I was continuing the tradition of Romanticizing landscape.

Indeed, it wasn’t until reading Geography as an undergraduate that my perception of landscapes – and importantly, my perception of those feelings themselves – altered. I began to appreciate them beyond their mechanical aspects (glaciation, tectonics, erosion etc.): as mental spaces. Thus, what began as my childhood embellishment of landscapes I simply liked has developed into a reflexive critique of those landscapes and my responses to them. Hence why I paint seemingly familiar scenes: these produce an eeriness which provokes reflection on the part of the viewer as to why and how society has historically come to regard landscapes in certain ways. I conjure scenes which question themselves as seen in our mind’s eye; they question the creation of “wilderness”, “nature” – and indeed, “Nature”.

Overall, whilst my inspiration still comes, as it originally did, from places I have been, this is now combined with an awareness – skepticism, almost – of why I respond to a certain view in a certain way. My paintings are less landscapes I like, and more landscapes as ideas which intrigue me. My paintings subvert rather than celebrate themselves.

Sholto Blissett

Garden of Hubris XVIII, 2021

oil on canvas on board

43 1/4 x 39 3/8 in. (110 x 100 cm.)

Q: Your Garden of Hubris series tackles the anxiety of climate change with such seemingly serene, symmetrical beauty. Yet upon a closer look, the marble stone structures are eroded by water or overcome by verdant foliage or tree trunks. How do you balance this tension in your compositions?

While I am painting in the immediate context of the climate crisis, my work is not solely a response to that. Rather, it deals with the broader theme of the Subject/Object relationship established between humans and ‘Nature’, and how that has influenced the development of many societies.

Q: Upon close inspection, one can discern what appears to be pencil draft marks on your paintings, delineating the space. Can you tell us about what the process of beginning a painting looks like for you?

As I’ve already said, I paint largely from my imagination – most of my ideas for paintings are thought up quite instinctively and impulsively. This involves an important distinction for me: I picture a view in my mind which I would like the painting to depict, rather than imagining the painting itself as a thing that I aim to paint.

As these initial mental-images are fairly ephemeral, I jot them down hastily in ‘plans’. These deal solely with the image’s linear perspective, just to see how the composition will come together. I’ll normally do this for several different ideas, sometimes taking elements from one and adding them to another, until I arrive at a composition that I am happy with. I know when I am happy with a composition if I feel excited to paint it. When this happens, I draw that composition in pencil on a primed and sanded canvas. This second ‘plan’ involves measuring and drawing up the depth, scale, and geometry. Then I paint. There’s a general, but no fixed order as to how I paint. The pencil lines are visible in the finished painting as I don’t want to cover them for the sake of it, if they do not need to be erased or painted over for the sake of the image then they will be left.

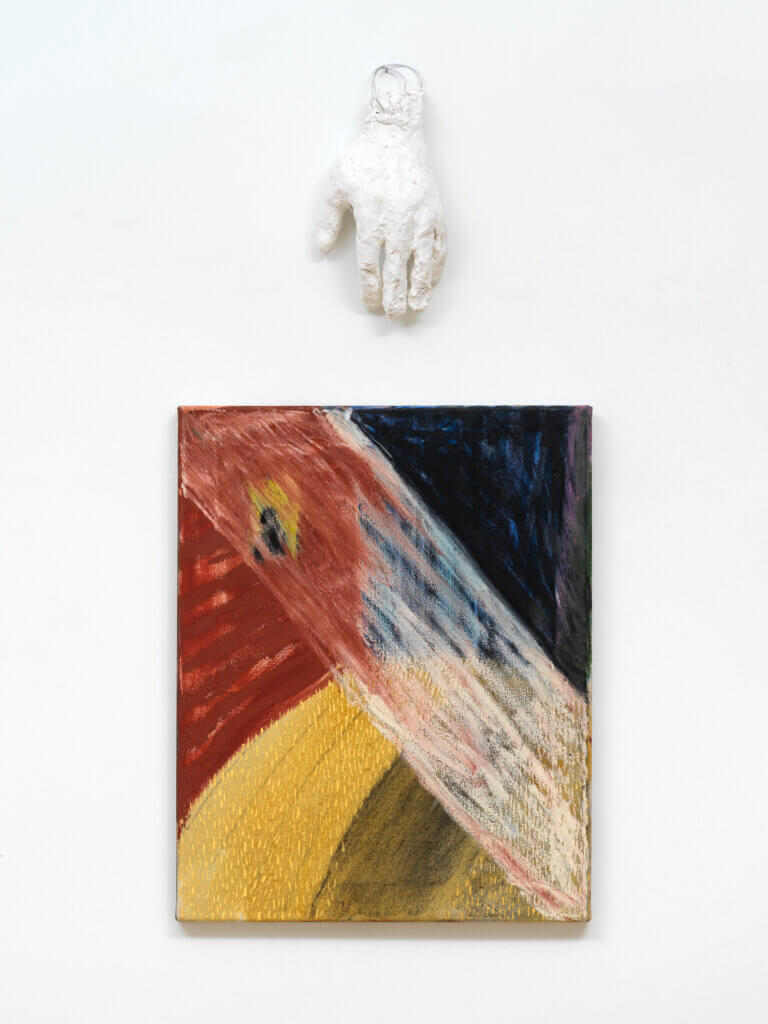

Emma Fineman

Backwoods, 2019

oil and charcoal on canvas; jesmonite plaster, and aluminum wire

painting: 20 x 16 in. (51 x 41 cm.)

sculpture: 10 1/4 x 5 in. (26 x 13 cm.)

London-based artist Emma Fineman paints and sculpts scenes from her memory, resulting in gestural imagery that unsettles conventional notions of time and space. In the face of contemporary tensions—including those wrought by digital interactions with the world—Fineman attempts to grapple with present human experience.

Q: The relationship between your sculptures and paintings appears clearly when considering how deeply textured each appears, be it via thickly layered paint, dense charcoal, or the rough finger-marked surfaces of your sculptures. When working between these various media, how do you decide what tool to pick up next? Can you describe how each medium aids you in your expression?

In painting, I often use materials that lend themselves to drawing. I am attracted to these materials as they capture a mark and energy on the surface quite well, and the act of using them feels more similar to writing, like jotting down an idea—a quick note to self. In many ways, my paintings are quite journalistic. They are a record of many moments and conversations all played out in one still frame.

Sculpture, on the other hand, has this amazing ability to address the physicality of space, rather than functioning as a portal as painting often does. Through sculpture, I am able to play with the physicality of the viewer, to encourage movement in the space, and hopefully a moment of discovery as they navigate the work. I utilize sculpture mesh and plaster gauze when working in sculpture. These materials allow me to bridge the gap between the two mediums. The mesh creates a grid-like structure which, in its own way, carries with it a mark or a gesture, a line that moves across the surface.

Emma Fineman

Immaterial, 2019

oil, charcoal, and gold leaf on canvas

76 3/4 x 112 1/4 in. (195 x 285 cm.)

Q: The scene in your 2019 painting Immaterial appears royal, magical, and otherworldly as a pink figure gestures over a white-swathed figure with a crown and yellow rays emanating from around their head. Could you describe this religious occurrence as you imagine it?

This work was created during a residency that I was completing in Brescia at Palazzo Monti. During this time, I spent many days visiting the church of Santa Maria in Solario. The visual of the lapis sky situated over a series of narrative frescos impressed itself upon me, and I began to think a great deal about this history of religious narrative paintings and more specifically of Leonardo da Vinci’s Annunciation painting at the Uffizi in Florence. In the Annunciation painting, there is a space between the angel and Mary that is so full of energy it is as if a third figure exists within the picture plane. I had a conversation with a friend that week about the annunciation story where a preacher had given a sermon in which she explained that the annunciation can actually be seen as the first instance in biblical stories of a woman’s right to choice. In this sermon, she pointed to the fact that the angel does not merely tell Mary “you WILL have this child,” rather the angel poses a question “will you have this child?” It is within that question that Mary has the agency of saying yes or no. She is given a choice.

This work attempts to capture the beginnings of agency, the ah-ha of individual thought, and the sublime encounter.

Emma Fineman

Configurations, 2021

oil and charcoal on canvas

59 3/4 x 75 in. (151 x 190.5 cm.)

Q: The forms in your painting Configurations are much less defined and more abstract than in your other work in this show. Could you describe the event in this painting?

This was a work that was made during a visit to San Francisco where I am from, originally. It had been well over a year since I had last visited and I was struck by the color and light there. I spent many days observing them from the road, moving through the landscape quite quickly. This painting is a journaling of that experience. It is a reflection on the familiarity of the palette there and the gesture of the landscape as it imparted itself upon me both during my childhood growing up as I remembered it, and also in the present moment of re-experiencing it after many years spent living elsewhere.

Brooklyn-based artist Madeline Peckenpaugh renders depth through layers of paint, transcending the boundaries of the flat canvas while rejecting formal perspective techniques. The paintings unfold through iterations of addition and subtraction, such as sanding and scraping. Through this process, coincidences and resemblances help the space unfurl as marks of paint become subjects themselves.

Q: The forms in your work oscillate between hard, flat edges and loose, gestural textures. How do you determine your varying approaches to shapes within your landscapes?

My approach varies from painting to painting, I don’t have the full idea of what the painting will be until multiple parts come together throughout the process. The looser and gestural paint is essentially me drawing and trying to figure out the space of the painting, gradually becoming more specific. The flat shapes usually have a specific role in each piece, such as collapsing the space or being used as a barrier to enter the painting. Using these multiple languages of painting helps to create and merge different textures and spaces into one, creating a new environment.

Madeline Peckenpaugh

Fertile Ground, 2021

oil on canvas

54 x 50 in. (137.2 x 127 cm.)

Q: You have mentioned that you draw inspiration from both urban and natural environments. How has your recent move to Brooklyn influenced the new paintings you have created in your Brooklyn studio?

I’m inspired by just my day to day being different, and the abundance of places and things to see and hear. However, I think it might be a little too soon to fully answer about The Brooklyn influence. Maybe it will start to show in a few paintings down the road.

Q: The interwoven lines in your painting Fertile Ground in conjunction with the dark green arcing triangles in the forefront create an optical illusion of deep space. Could you share how this environment evolved and what you envision is happening here?

This painting took the longest to come together in the group—I think it being the smallest in scale made it the most difficult for me. It also had previous layers I wanted nothing to do with, so it went through a process similar to Standing Still, scraped down, sanded, almost discarded etc. It did start to surprise me when it was no longer precious, and it started to evolve into something totally different. The deep space in Fertile Ground came from the sort of suspended river rushing through the foreground. I wanted to mimic that movement or narrative throughout—almost like weaving. The dark green shapes in the foreground felt like their own plant species, living in their own environment. I didn’t want them to necessarily intrude, but they aren’t grown from the same crop.

Madeline Peckenpaugh

Standing Still, 2021

oil on canvas

64 x 52 in. (162.6 x 132.1 cm.)

Q: Since you build your paintings layer by layer and improvise as you go, what was the most surprising aspect that arose from one of your paintings in this show?

I’d say the painting that most surprised me was Standing Still. That painting was sanded down and built back up multiple times, and each time there would be new ghostly layers of paint from the past. It really made the bottom of the painting feel very atmospheric, even though it’s technically the “ground” of the painting. I played off that groundless aspect with the title, and by having a heavier sculpture-like structure standing on it.

Sholto Blissett, Emma Fineman, Madeline Peckenpaugh (December 10, 2021-January 22, 2022) at Alexander Berggruen, New York.

Photos: Dario Lasagni