By Flora Blissett

February 2023

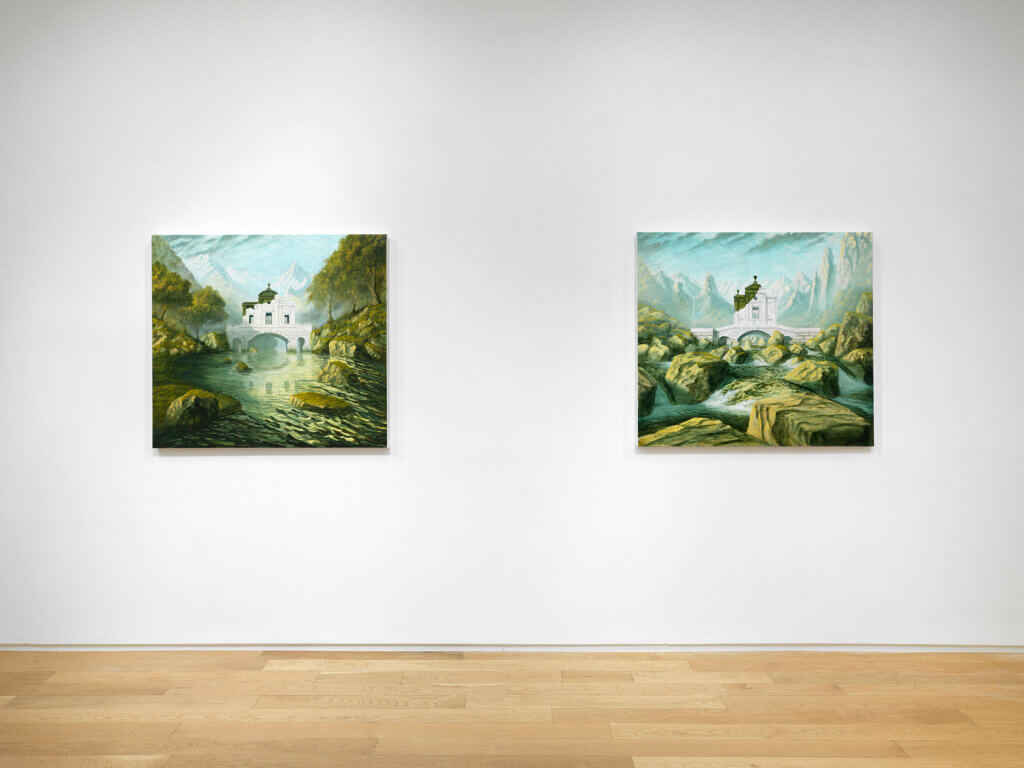

Installation view of Sholto Blissett: Rubicon (January 25-February 22, 2023) at Alexander Berggruen, NY.

In Sholto Blissett’s newest series of eight large-scale oil paintings, free-stone upland rivers course choppily past us, their way punctuated by moss-thick boulders, flanked by picturesque trees, and traversed by elaborate bridges, all against a backdrop of grand mountains or expansive vales. There is conceptual action, too. Ideas fed Rubicon like tributaries, culminating in an exploration of humankind’s relationship with nature – past and future.

We might consider the phrase ‘crossing the Rubicon’ a central idea. After all, it is a stock-phrase, referring less to its etymological historic event and more to its metaphorical meaning: achieving an impressive feat; making a political advance; conquering nature. But this did not inspire Rubicon; indeed, Sholto curtails and undermines this phrase. He only landed upon this title a few weeks into starting these works, when listening to a history podcast. What initially inspired Sholto, and what he set out to paint, was “rivers he’d like to fish”.

Hence his truncation of that familiar phrase. Sholto turns his – and our – attention to the river. Extracting the river from the phrase separates it from a human-oriented narrative, thus revealing our historic complacency in human interferences with nature and the linguistic trick of metaphors that distract our gaze from the thing itself. Whilst we understand what ‘crossing the Rubicon’ means, we are faced with a new question. What is it to view Rubicon?

In one sense, it is to view Sholto’s love of nature. His free yet precise brushstrokes attest to his observations made while walking, fishing, swimming, and kayaking, reinforced by reading Ted Hughes, Robert MacFarlane, and Edward Thomas, among others. Rivers are the most conscientiously painted feature. They are united by a geographical logic: from mountain-source to mid-stream torrent, to the distant silver-blue meanders. This logic lends the paintings realism; we can almost hear their rushing waters.

However, an undercurrent of tension runs throughout Rubicon: Sholto’s attentively depicted natural features appear in overtly fictional scenes. A rift emerges between ‘reality’ and ‘fiction’, a moment of suspense, like the undertow of a riverbank or step. This rift exaggerates to breaking point our tendency to construct rather than record landscapes – both visually (as paintings and maps) and physically, sculpting the nature to our desires. To view Rubicon, then, is to look into a mirror held up to this confluence of nature and mind. These are not landscapes, but paintings about landscapes. With this revelation comes self-reflection, and the mirror is shattered as quickly as it is looked into.

Sholto Blissett

Rubicon V, 2022

oil on canvas

63 x 78 3/4 in. (160 x 200 cm.)

The focus of Rubicon’s mirror-holding is the river. For centuries and across cultures, humans have ‘landscaped’ rivers to the point of near obliteration, turning them into things which they are not. Rivers course through our imagination as they do the land. We have deified water to make its intangibility and capriciousness explicable. We have metamorphosed water in language: ‘to cross the Rubicon’ means to do something grand. In Christian scripture water is life. From Homer to Melville, seas are transformative spaces. Not understanding water yet desiring to hold it still, we have made it something it is not. Likewise, we have physically mutated rivers: siphoning them for crop irrigation; drowning them with dams; using them as waste repositories. We treat Earth’s waters unthinkingly – rather, thinking only of ourselves.

The incongruously placed bridges interrupt that thinking. Any initial impression of these bridges’ grandeur is undermined by asking: what’s the point?; what are they doing here? The blend of Classical and Gothic architecture places them ambiguously between functions: secular, religious, private, or communal? Their once perfectly white foundations are stained with riverweeds and, like the boulders and riverbed themselves, will be eroded. Present but purposeless, these are our follies. And they are in decline. Ironically, we seem to have missed our own red-flags, fluttering upon our careless designs. For the elaborate finials are being overcome by greenery. This mock-topiary encroaches from the left, mimicking western script; but this time, the writing is nature’s story, not our imposed myths and idea(l)s. Precedence is given to nature over human folly within these paintings, and in our minds having viewed them. I’ve never said this to Sholto, but while I see his paintings as interesting for their inclusion of the buildings, I think they would be more beautiful without them. I think that is maybe the point.

Palladian Bridge (1736–37, Grade I listed) at Wilton House, Bath, UK.

From this point of ruination, we may contemplate the future; as indeed do the perspectives of Rubicon IV and V, the only paintings turned downstream. These contrast visually and symbolically to the other six paintings’ upstream views, wherein Sholto depicts the geographical forms through which the rivers have passed and, metaphorically, the history of the landscape genre. These landscapes’ pasts are well-defined, painted from informed knowledge. Downstream, however, the rivers’ futures are less defined – visually and abstractly – as forms dissolve into misty articulations. As the river’s momentum slows in meanders, the tone shifts into a future space and tense. Where gazing upstream encourages reflection upon our past and current relationship with nature, peering downstream may inspire rumination about the future, undefined in paint and knowledge.

To view Rubicon is to view the history of our relationship with nature; but it is also to turn towards that dynamic’s future. Rubicon realigns our thinking towards the river, centralized in title and composition. For all our mythologizing of waters, we have lost the ability to revere the river itself. We should not abuse the privilege of its inspiration, but should (re)learn to admire them, rather than what we can use them for. Sholto starts this process in the very place where it all started to go wrong: art. Though Rubicon, like a river, was formed from wider historical actions, it exercises its own power, creating action going forward.

Sholto Blissett

Rubicon III, 2022

oil on canvas

78 3/4 x 63 in. (200 x 160 cm.)

– Flora Blissett is a Gallery Assistant at a contemporary London gallery. She studied English at the University of Oxford, where she continued to gain an MSc in the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, before moving to the Courtauld Institute to read the History of Art. Through writing, Flora aims to promote access and education to art, starting with the celebration of her brother, Sholto Blissett.

This essay was published on the occasion of Alexander Berggruen‘s exhibition Sholto Blissett: Rubicon (January 25-February 22, 2023).

Installation view of Sholto Blissett: Rubicon (January 25-February 22, 2023) at Alexander Berggruen, NY.

Photos: Dario Lasagni