Darren Bader

cow with/and tambourine; cow and/with flute

dimensions variable

In Bader’s words, his work included in Animal Kingdom cow with/and tambourine; cow and/with flute “consists of at least* three elements: a cow, a flute, a tambourine. The cow** can be any free-roaming and/or free range member of the species Bos primigenius. It’s recommended the flute be a Western concert flute (Boehm flute). The tambourine should be a tambourine should be no smaller than 8 in. (20 cm.) and should have a drum skin***.

“Cow and flute should be placed in relative proximity to one another, roughly conforming to a person’s ability to see both elements without having to move her/his/their head. The same applies to cow and tambourine. Tambourine and flute shouldn’t be near one another. The work has no recommended duration.

“*The cow in the work may likely be in the presence of other cows. If cow = cows, that is ok.

**Humane treatment of the cow(s) is of the essence.

***It’s recommended the drum skin be made of animal skin.”

Q: What do you hope an online audience will take away from cow with/and tambourine; cow and/with flute?

A: Whatever they do. That’s ideal.

Q: Where did the idea for cow with/and tambourine; cow and/with flute originate? Could you elaborate on your process?

A: Nothing too interesting. A notebook and habitual nature of thought. Or so I remember.

Q: How do you think about cows’, flutes’, tambourines’, and animals’ places in our cultural lexicon?

A: As one person among many who shares much with many (though not many more).

Q: What role does music play in this work?

A: I think you solved a riddle I didn’t realize I’d posed.

Q: What roles have animals played in your work across your practice?

A: Arguably too many. I thought their physical presence could be justifiably sculptural. I’ve since grown to find that conceit dubious, and perhaps reckless. Animals as lexical and visual (as distinct from sculptural (and perhaps even material(???)) objects are inexhaustibly meaningful.

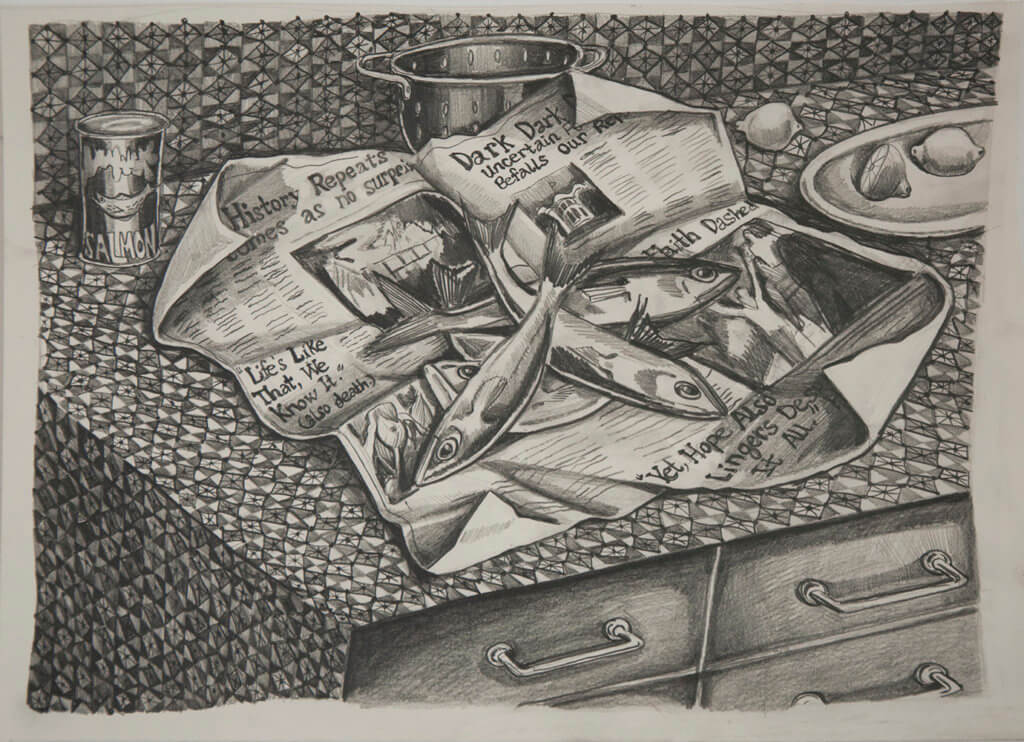

Nikki Maloof

Fish and Headlines, 2020

graphite on paper, unframed

11 1/2 x 15 1/2 in. (29.2 x 39.4 cm.)

Maloof’s 2020 still lives included in Animal Kingdom suggest familiar yet elusive domestic scenes tinged with both hopeful and despairing references to the year’s current events.

Q: How do animals function within your work?

A: Though I find my relation to them shifting, most often I think of the animals as stand ins for my own experiences and mental states.

Q: Can you share the inspiration for the text included in your 2020 graphite works on paper Fish and Headlines and Bird Cage?

A: These days it’s particularly easy to find inspiration for my dread-filled headlines, just look at any news outlet.

Q: How do you create your still lives? Do you begin with a staged or real-life scene, an image, or your imagination?

A: They are mostly from my imagination, but I bring in props and images when I need an extra dose of specificity.

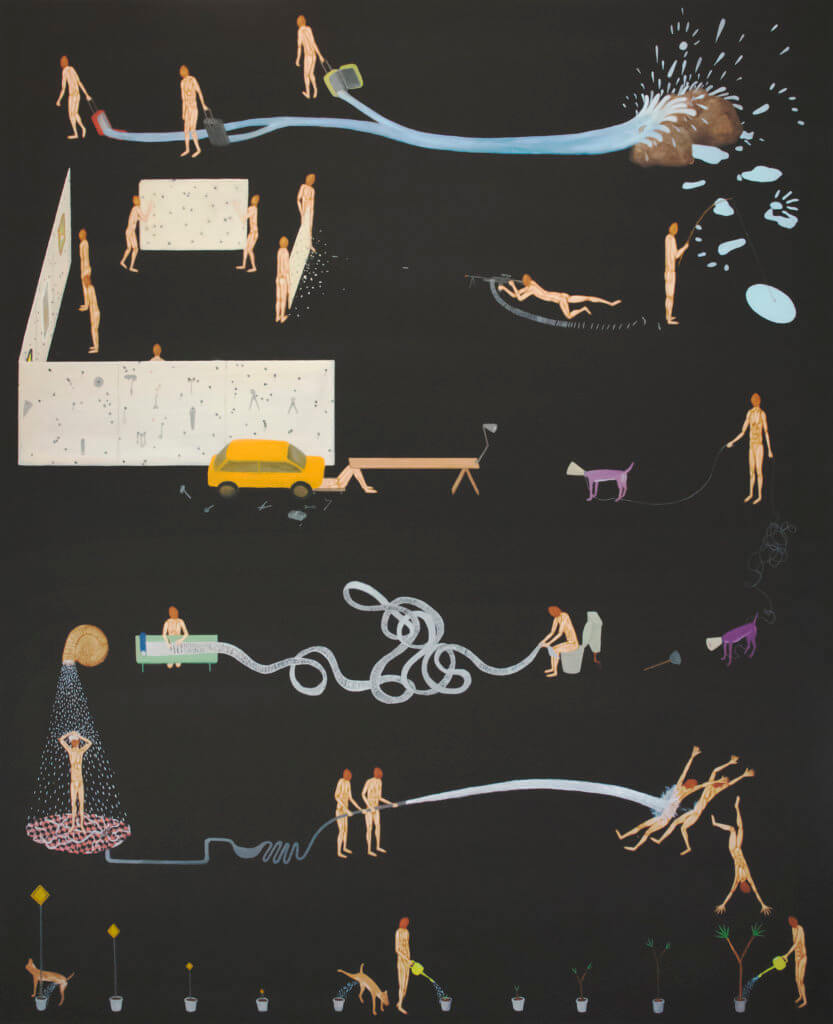

Akira Ikezoe

Coconut Heads and Water, 2017

oil on canvas

62 x 50 in. (157.5 x 127 cm.)

Ikezoe seamlessly connects distinct narratives in his paintings, drawing from a curiosity of how humans interact with their outer- and inner-worlds.

Q: How do animals exist within your work?

A: Sometimes I feel that my existence in this world is more like an animal rather than a human being in this society. Those animals could be my self-portrait.

Q: What was your starting point for Coconut Heads and Water?

A: I had some ideas in my mind, such as the similarity between cones on the dogs’ heads and the table light, the fish becoming bullets, and plants and traffic signs growing to the opposite directions. Those ideas as a starting point, I connected them to create a linear story.

Q: How do the distinct scenes rendered in this painting relate to one another?

A: This drawing process also works like a word association game. When I draw something, the line reminds me of something else, and I draw it. Then again it reminds me of something else. The object that I draw tells me what to draw next. It’s like making an exquisite corpse by myself. This process creates domino effect-like movements. Visual narratives in the Coconut Head series are reflecting this movement—one thing happens, and everything else happens automatically.

Q: Do you have a narrative mind for your Coconut Heads series?

A: Yes, I do. My motivation to make this painting series is to create a story between similar visual characteristics just like ancient people did to grasp this universe—if people from 300 years ago find a huge rock that is shaped like a genital organ, they worship it as a symbol of reproduction; if a person runs faster than the others, the person is considered an avatar of the fastest animal in the area. I think humans have an inherent desire to invent a story between similar objects. It is an unscientific and irrational way to see this world, but I believe we are still doing it.

Q: How do you think about your works that combine the human and animal body?

A: Just like our surroundings where nature and our culture have always been invading each other, I recognize a contradicting coexistence of culture and nature in my body—the conflict between aging and anti-aging, addiction and chemical therapy, our animal instincts and effort of civilizing ourselves, etc. I sometimes want to take this chaotic being out of my body and visualize it.

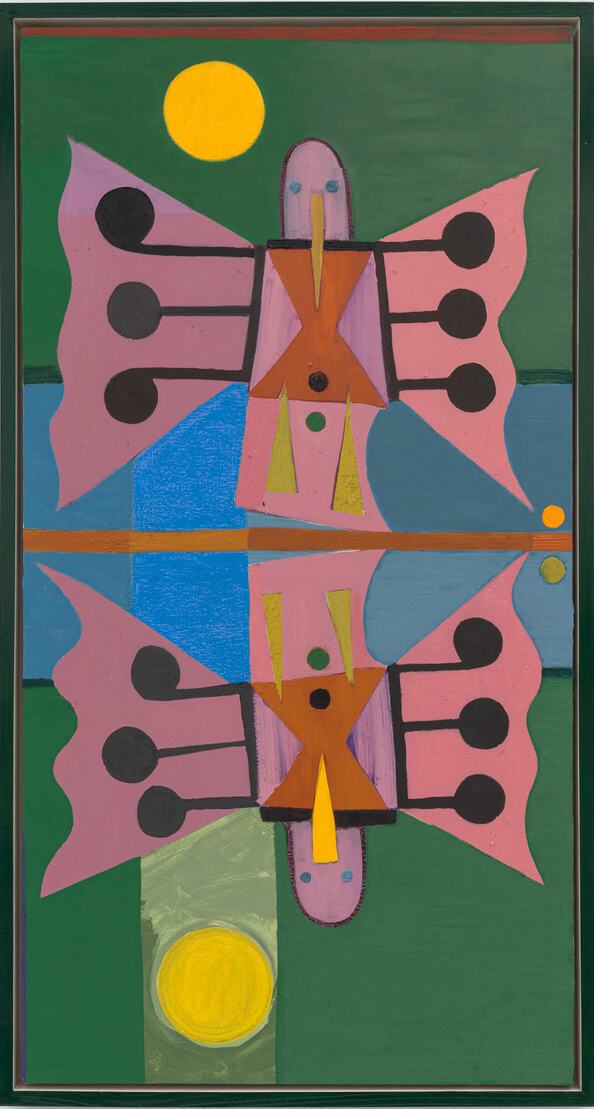

Austin Eddy

So Mild Is The Monotone Evening, Wrapped Around A Slow Land, 2019-2020

oil, flashe, colored pencil, paper on canvas, in artist’s frame

48 x 26 in. (121.9 x 66 cm.)

Austin Eddy paints in mixed media–such as oil, flashe, colored pencil, and paper on canvas–to create poetic compositions in which the narratives are driven by animals.

Q: Can you tell us about the title of your 2019-2020 work So Mild Is The Monotone Evening, Wrapped Around A Slow Land?

A: The title references an excerpt from a Paul Verlaine poem.The painting seeks to portray how Verlaine wrote about the time of day when the light reaches a certain point in the sky, causing the sky and the water to appear to blend or flatten. Things start to become one. In a way, the bird is mimicking the sky and water, and it is becoming one with itself. The slowness signifies the importance of the moment.

Q: What does working in mixed media–such as oil, flashe, colored pencil, and paper on canvas–lend to your process?

A: Working in mixed media is part of the process. I start the paintings by mounting paper to the stretched canvas and sealing it with matte medium. After that, I draw the composition in charcoal and colored pencil. Then, I underpaint in Flashe. The paper provides a smooth, but still semi-toothy, surface, while the flashe paint’s matteness provides absorbency and further tooth. After the underpainting, I’ll tweak things with colored pencils before painting in oil. There are often areas of the painting where you can still see the colored pencil, flashe underpainting, and sometimes even the paper base layer.

Q: How do you determine what to articulate and what to abstract in your work?

A: Oftentimes, I do lots of small colored pencil drawings and ink wash drawings to work out compositions. Through that process, things start getting more and more simplified and more information is omitted. The process, in a way, determines what is simplified and abstracted. I am trying to pull back things into reality to make things more recognizable and relatable without giving away everything and to leave room for people to find their own experience of the scene.

Q: What role do animals play within your work?

A: Currently, the animals provide a character to construct the narrative around. A type of skeleton for emotion. They typically exist as metaphors for aspects of the human condition or an experience. Most often in the paintings, the birds are meant to be examining an idea of self reflection, longing, or a type of melancholy. The new paintings are trying to capture a sense of stillness in motion. Though the narrative may be masked, I try to focus on the tone and mood through the color and truncation of space.

Haley Mellin

Self-Portrait (with Orange Cat), 2020

acrylic, tempera and gouache on canvas, in artist’s frame

16 1/2 x 12 1/2 in. (41.9 x 31.8 cm.)

Haley Mellin is inspired by conservationism to act and paint digital-real artworks that often portray the animals she has encountered in her daily life and while on conservation trips.

Q: What role do animals and the environment play in your work?

A: I spend my days painting and conserving land. Often, I am on land conservation calls regarding contracts, due diligence reviews, legal reviews or matching funds for projects while I am painting. For example, this year, I made 8 paintings and supported the conservation of 7,040,000 acres of land. As an artist, I will never be able to make anything as exceptional as an animal, but I can act, with thought, and keep animals from going extinct. In a way, I have a small hand in the continued presence of these places and these animals. My father often says, how do you invent anything as exceptional as a giraffe? I would say, in my daily life, the environment and art are as linked as can be.

Q: What was your inspiration for drawing an anteater?

A: The inspiration for the drawing came from seeing a Giant Anteater while walking in the Pantanal in Brazil, which is the largest wetland in the world and spans five countries. I was on a trip with my father, one of my conservation heroes, Dr. Russell Mittermeier and his daughter. Russ was teaching me the necessity of the large-scale tropical forest conservation to our global hydrological cycle. One day we came around the corner, and there was a Giant Anteater looking for his next meal. From such creatures I understand the necessity of conserving large tracts of land, one anteater needs a good few miles to roam.

Q: What was your inspiration for the choice to call attention to the color of the cat rendered in your Self-Portrait (with Orange Cat) in its title, while the painting is rendered in black-and-white?

A: I was hoping that you would ask! I thought the title would bring color to the grey painting. He is an orange cat named Sunkist, after the brand of orange, and he showed up a couple of years ago when I returned from the trip to the Pantanal. I have been painting in greys for five years and was seeing this as a return to color!

Q: Can you elaborate on the stylistic differences between Self-Portrait (with Orange Cat) and Giant Anteater (Pantanal, Brazil)?

A: I am getting my feet wet as a young painter and I like to try different things. One was done from life, and one from a digital photo. If I am working from direct observation, the painting tends to be looser. If I am working from a digital photo, the painting is more exacting.

Q: How do you think about your hand-rendered works’ relationship with the digital realm in regard to perpetual technological innovation?

A: Since photo-real painting is an age-old medium now, during school I focused on making digital-real paintings. It was a studious period, and I painted and glazed in a digital real manner. As a technical challenge it was somewhat of a Zen practice, as I know what the end result needed to be. Overall, I think most painters learn technical skills or copy approaches before loosening into their own mature style, which is a combination of their head, heart and hand, and the person they become based on decisions and life choices. I hope my way of painting will become increasingly authentic within the technical support available.

Susumu Kamijo

Before The Storm, 2020

flashe vinyl paint on linen

24 x 20 in. (61 x 50.8 cm.)

Susumu Kamijo playfully renders the aspects of his life which fulfill him most–his pet poodle and quite moments watching the horizon–in bright colors and deconstructed, abstracted forms.

Q: What inspires you to paint poodles?

A: I’m addicted to the form and shape of well-groomed poodles. When I first started drawing, kind of as a joke, I drew in tribute to my pet poodle. I had no idea how addictive it could get!

Q: How do you determine the environments in which you place the poodles you paint?

A: I usually paint a poodle or poodles first, then ask myself what kind of environment the poodle wants to be in. Mostly, they are in a vast landscape with a horizon line in it. I guess this is because one of my favorite things to do is to stare at a horizon line for a long time, sitting on a comfortable chair, sipping a beer or a pina colada.

Q: What role do animals play in your work?

A: When I’m painting or drawing, I’m always trying to make decisions instinctively. When I make plans or calculate the trajectory of work, the work seems to fail miserably. So, I’m trying to be like an animal or beast with sharp instinct when I’m in the studio, as much as I can.

Q: Can you elaborate on the title of your 2020 painting Before The Storm?

A: I have to admit, I get really excited before a storm or heavy snow fall is coming. For me, the poodle in Before the Storm contains that kind of excitement and guilty pleasure.

Animal Kingdom Checklist:

https://bit.ly/ABAnimalKingdom

Animal Kingdom will run at Alexander Berggruen (online only) from June 26-August 29, 2020. We will be pleased to share pricing and availability upon request. For all inquiries, feel free to contact the gallery at: info@alexanderberggruen.com.