Online Only

June 26-August 29, 2020

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST:

https://bit.ly/ABAnimalKingdom

John Alexander

Darren Bader

Elana Bowsher

Christopher Brown

Anne Buckwalter

George Condo

Austin Eddy

Jeff Elrod

Walton Ford

Danny Fox

Lucian Freud

Dominique Fung

Keith Haring

Michael Hilsman

Damien Hirst

Akira Ikezoe

Susumu Kamijo

Sean Landers

Robert Longo

Brendan Lynch

Nikki Maloof

Tom McKinley

Haley Mellin

Ryan Mosley

GaHee Park

Paola Pivi

Josh Smith

Aya Takano

Emma Webster

Darryl Westly

Donald Roller Wilson

Alexander Berggruen is pleased to present Animal Kingdom, an online only exhibition (June 26-August 29, 2020). This group show explores how animals can function within contemporary art. It puts in conversation a seemingly disparate group of artists spanning a multiplicity of geographic locations, traditions, and conceptual commitments, united by a fascination with animals as an iconographic feature, formal motif, or even medium. It suggests that animals operate with elasticity. For some, animals appear to act as purely aesthetic phenomena, used as colors and shapes to be arranged within the artist’s mind. For others, they serve as symbols and archetypes, emblems of beauty, comfort, intimacy, and hope. In yet another context, they serve as reminders of the artifice implicit in modern life, or perhaps a bridge between humans and an inanimate world.

Certain figurative painters have viewed humans and animals as similar subjects. Lucian Freud has said: “When I become immersed in the process of painting someone, I can lose their relationship to me and just see them as beings, as animals […] in the natural sense.” Freud was also “very fond of horses”, after having attended school on a farm as a child, and executed numerous equestrian portraits over the course of his career. (1) Freud’s 1983 Head of Success II depicts a horse who appears to be glancing back at the viewer.

Animals as figures can be core to an artist’s personal visual language. Keith Haring has stated: “I was thinking about these images as symbols, as a vocabulary of things. […] In different combinations they were about the difference between human power and the power of animal instinct.” (2) In Haring’s 1981 Untitled work on paper, a snake intrudes into the outlined picture plane, hissing at a figure while a television smiles above the scene, seeming to delight in this figure’s fear. Christopher Brown’s 2020 painting The Summer of ‘61 seems to access memory – specifically, a moment of trauma. In a scene not unlike Haring’s, a bear catches a car traveler off-guard. Only the crux of this fearful recollection seems sharp, while its surrounding details invoke a haze.

Certain figurative painters have viewed humans and animals as similar subjects. Lucian Freud has said: “When I become immersed in the process of painting someone, I can lose their relationship to me and just see them as beings, as animals […] in the natural sense.” Freud was also “very fond of horses”, after having attended school on a farm as a child, and executed numerous equestrian portraits over the course of his career. (1) Freud’s 1983 Head of Success II depicts a horse who appears to be glancing back at the viewer.

Animals as figures can be core to an artist’s personal visual language. Keith Haring has stated: “I was thinking about these images as symbols, as a vocabulary of things. […] In different combinations they were about the difference between human power and the power of animal instinct.” (2) In Haring’s 1981 Untitled work on paper, a snake intrudes into the outlined picture plane, hissing at a figure while a television smiles above the scene, seeming to delight in this figure’s fear. Christopher Brown’s 2020 painting The Summer of ‘61 seems to access memory – specifically, a moment of trauma. In a scene not unlike Haring’s, a bear catches a car traveler off-guard. Only the crux of this fearful recollection seems sharp, while its surrounding details invoke a haze.

Other artists choose to render only the suggestion of an animal’s presence. Ryan Mosley has said of birds in his paintings: “I think the birds are […] an evolution that initially came from this idea of being able to reference something figurative, without being overly articulate with it.” (3) As we see in Mosley’s 2020 Birds, most of the flamingos’ bodies exist beyond the edges of the painting, while the dense placements of their technicolor curved heads and necks suggest a cohesive flock.

In other examples within Animal Kingdom, animals can represent mythical or magical beings. Emma Webster’s 2020 Narcissus depicts a horse-like creature enacting the role of the hunter in Greek mythology, as it becomes increasingly obsessed with its own reflection. The aspect of theatrics is core to Webster’s practice, not only in subject matter, but also in process. Webster bases many of her compositions on sculptural dioramas she constructs and lights dramatically, as studies for her ultimate painted compositions.

While Dominique Fung also places animals in surreal settings, her animal figures act as “witnesses” to confront white supremacist and Eurocentric fetishized views of East Asian culture. Fung has claimed that her animals aid in questioning her audience: “How are East Asian objects viewed? How is an East Asian person viewed in art history? What happens when there is very little to no representation in stories and media of the yellow person?” Fung’s 2020 Sitting The Month tells a story of childbirth and recuperation in relation to the superstition in Chinese culture of zuo yue zi, or “sitting the month” to rest after childbirth. Where vessels act as representations of the body, the leftmost ceramic gives birth out of an opening, painted with a faded fish’s mouth, to a smaller vessel, suggesting femininity and antiquity–both tropes of 19th-century Orientalism. The resting porcelain cow to the right is successfully observing “sitting the month”by restoring her chi as seen in the overflowing vessel on top of her.

Paola Pivi similarly uses animals to interrogate reality, using her work to offer imagined narratives that exist beyond the commonplace. In Pivi’s 2019 Long time no see, two brightly colored bears embrace in an envisioned future in which they have adapted to the altered climate by growing feathers. Pivi’s 2008 sculpture Untitled (muskox) eloquently attracts the viewer toward the animal known for its eponymous musky odor by, here, mounting the creature on a pile of a more human-centric scent: aromatic coffee beans. Pivi’s muskox encourages the viewer to investigate just as its live counterpart in nature might aim to attract mates.

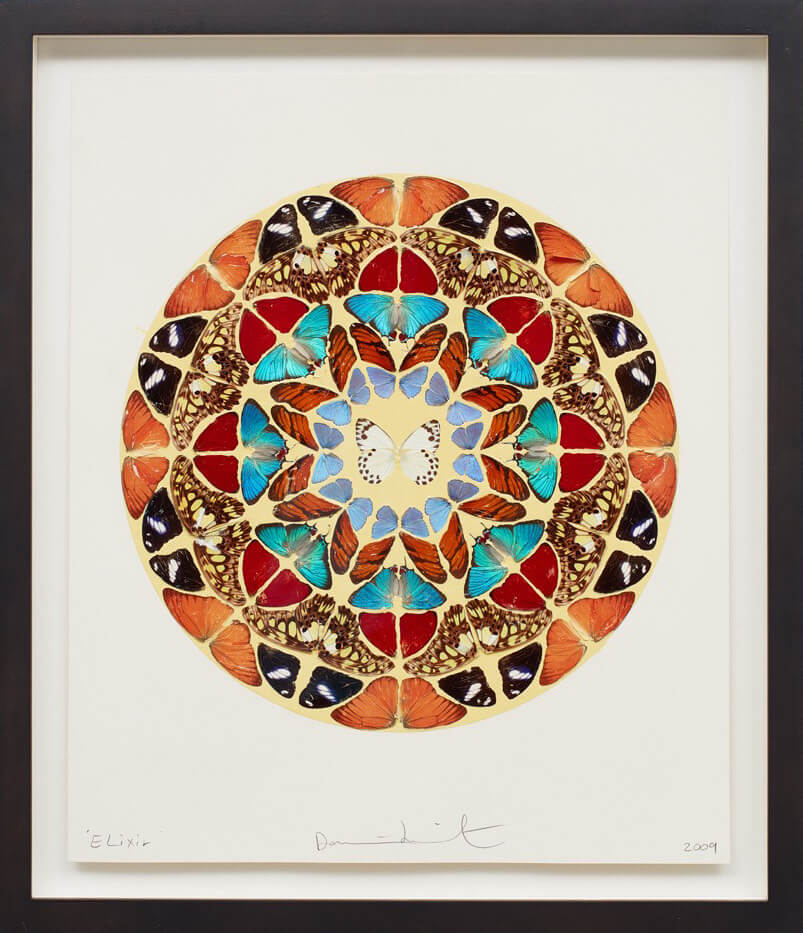

Damien Hirst, who also uses actual animal bodies in his work, has stated that, “Rather than be personal you have to find universal triggers: everyone’s frightened of glass, everyone’s frightened of sharks, everyone loves butterflies.”(4) Hirst’s 2008-2009 Elixir employs butterfly wings stuck to paper with household gloss, almost as though these elegant airborne creatures were accidentally caught in the painting. Hirst embraces the naturally occurring symmetry of each side of one butterfly’s wings and elevates this phenomenon in his grander, constructed sublimely symmetrical composition.

Darren Bader’s cow with/and tambourine; cow and/with flute takes a more conceptual approach to animals in sculpture. In Bader’s words, “Cow and flute[/tambourine] should be placed in relative proximity to one another, roughly conforming to a person’s ability to see both elements without having to move her/his/their head.” The artist encourages the collector to experience the presence of these instruments in relation to a cow or cows, at different times, in order to regard animals’ places in our cultural perception. The collector observes a unique demonstration of time passing, marked by the moments at which the cow is exposed to a tambourine or a flute.

Animal Kingdom surveys how animals can exist within contemporary painting, drawing, sculpture, and conceptual art from the past four decades. Whether animals are portrayed or employed as media, the works in this show reflect how contemporary artists have conceived of animals as subject matter in distinct ways.

Animal Kingdom ran at Alexander Berggruen (online only) from June 26-August 29, 2020. The exhibition’s preview, with pricing and availability, is available upon request. For all inquiries, please feel free to contact the gallery at: info@alexanderberggruen.com.

(1) Lucian Freud with Michael Auping in Lucian Freud: Portraits, exh. cat., the National Portrait Gallery, London and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 17 April 2012.

(2) Keith Haring with David Sheff in “Keith Haring: Just Say Know” in Rolling Stone, 10 August 10 1989.

(3) Ryan Mosley with Harriet Thorpe in “Ryan Mosley: interview” in studio international, 3 July 2014.

(4) Damien Hirst, Damien Hirst: I Want to Spend the Rest of My Life Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now, London, 2005, p. 132.

Through nearly 50 works by more than two dozen artists—including Lucian Freud, Walton Ford, and Paola Pivi—this online show explores the myriad creative attitudes that inform how animals manifest in contemporary art. Specific contexts explored in the exhibition range from domestic realms inhabited by pets and livestock to the wild landscapes known to bears, elephants, anteaters, and beyond.

Spanning the past four decades, the paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and other types of art on view in “Animal Kingdom” coalesce into a spectacle as elegant and chaotic as the natural world they evoke.

Alexander Berggruen is pleased to share mini interviews with select artists included in our exhibition Animal Kingdom (June 26-August 29, 2020).